I’m currently sitting here with Intellij IDEA IDE open with 3 workspaces (different clones of the Trailblaze project). In each one of them I’m using Firebender with the Claude Sonnet 4.5 model.

As I’m writing this I just toggled back over to IDE and made sure all my agents are still running.

I’ve been hesitant to write this post because things keep changing so fast. But I’m doing it now to try to capture where I am today, knowing that things will change.

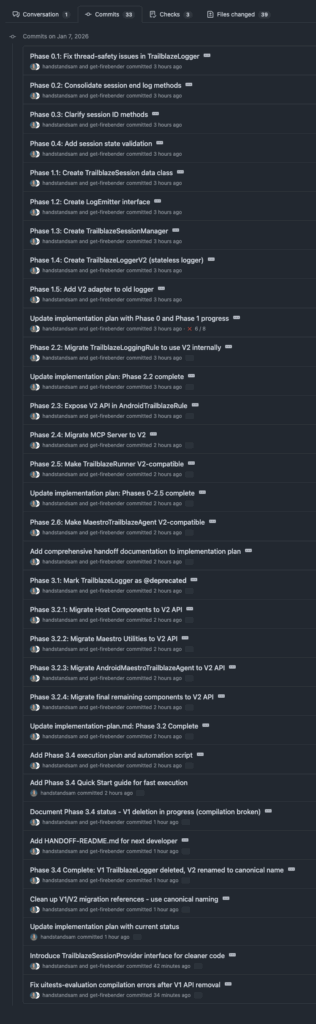

I’ve started using the Research, Plan, Implement (RPI) strategy and it’s working really well for me. I don’t know if I’m doing it “right”, but I tell the agent the problem, tag the appropriate files and ask the agent to create a research.md file for me with detailed information. I then look that over, and ask it to create an implementation-plan.md file which will contain detailed implementation steps that I can hand off to another developer or agent to implement. I ask it to lay out each incremental step and commit changes for each successful step of the plan. If the context window is getting too full then I have the agent dump all of its progress back into the implementation plan and tell it to hand it to another developer to finish.

Current Examples of How I’m Using This Strategy

To give you an idea of how I’m using it, here are some examples that are currently in progress.

Example 1: Refactor/Cleanup TrailblazeLogger

Trailblaze (UI Test Automation Framework) originally was just used in JUnit tests, but we have added the ability to run tests via our desktop application. This meant we needed common functionality in both places, but we had just put the existing code that was meant to be used during JUnit test lifecycle and make it work in the Desktop app. While that’s great that it worked, the code that is there now is pretty convoluted, so I’m using this strategy to untangle it. It ends up being a lot of small commits, but it’s easier to see what happened myself and for the agent. At the end I just review the final PR like I would by looking at the final changed files, and give feedback based on that. Right now these are the commits in that PR so far 😲

Example 2: Implement a GUI editor for Trails (trail.yaml files)

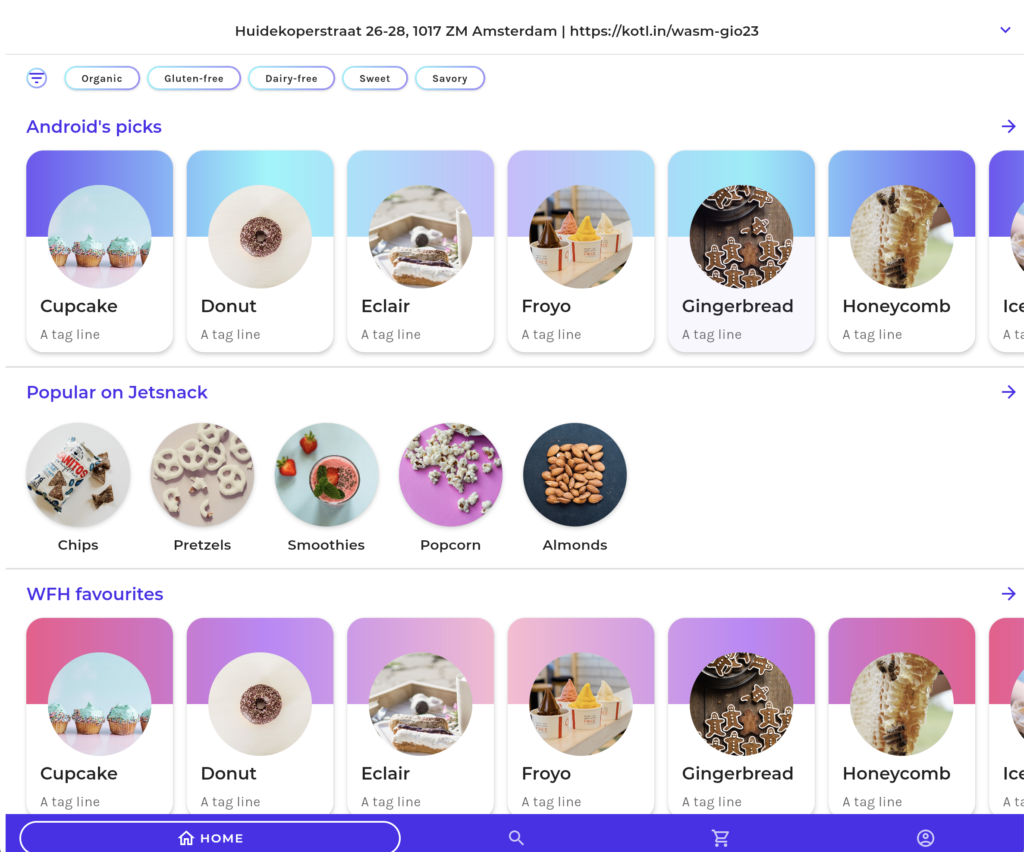

There is currently a way to view the yaml in plain text, but I wanted a way for users to be able to edit it in a visual way that makes sense to an end user and avoid syntax issues. This would include drag and drop support for re-ordering items as well. I’ve been using agents to build this Compose desktop app (and Compose Web (WASM)) UI for a while and it just works so well. I do get in there sometimes and clean up wiring and things, but during prototyping I just let it run.

Conclusion

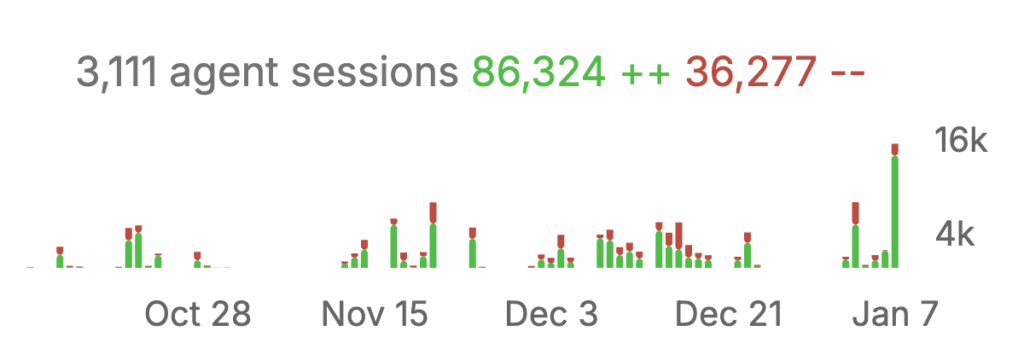

I’ve been using Firebender a lot over the last few months 👇

I’ve gone through phases where I’m using Claude Code as well. Overall for coding Kotlin I’ve had the best luck with the Claude Sonnet 4.5 models. I’ve also tried Claude Opus 4.5, which was great, but it’s more expensive and it didn’t seem to perform much different, so I’ve just stuck with Sonnet. I just really like the IDE integration with Firebender. So I’ve been sticking with Firebender for now.

I’m curious what my workflow will be next week or next month. Who knows 😂.