If you are building a Kotlin Multiplatform library which will be consumed by an existing iOS application, using a framework is a great way to do this. Frameworks are typically compiled for a specific target architecture which can then be run on an iPhone, iPad or iOS Simulator on your Intel Macbook.

If you are going use your Kotlin Multiplatform library as a framework in an existing app, you will want to provide a “Fat” framework which will contain both Arm64 and X64 architectures. This article contains the configuration I used to build the “Fat” framework. This is not a full build.gradle.kts file, but just the additional parts needed for a Kotlin Multiplatform project to build a “Fat” framework.

⚠️Use an XCFramework instead ⚠️

This “Fat” framework method no longer works with XCode 12+. Use an XCFramework instead.

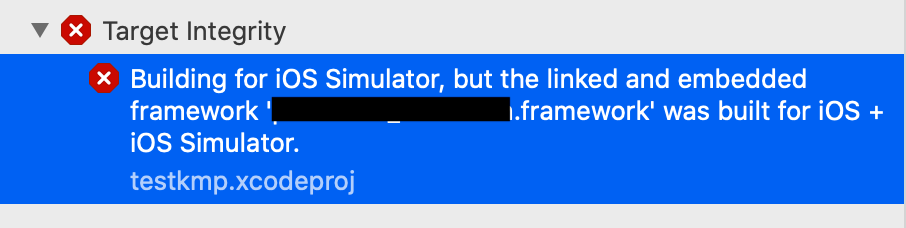

I ended up with this Error Message in XCode 12.4: “Building for iOS Simulator, but the linked and embedded framework ‘my_library.framework’ was built for iOS + iOS Simulator.”

This Stack Overflow post shows you how to create an XCFramework from your two frameworks, and I’ll follow up with a blog post on how to do it with an XCFramework a bit later. This solutions ends up combining the two frameworks into a single XCFramework.

xcrun xcodebuild -create-xcframework \

-framework /path/to/ios.framework \

-framework /path/to/sim.framework \

-output combined.xcframeworkCustom Gradle Task to Build “Fat” framework

import org.jetbrains.kotlin.gradle.tasks.FatFrameworkTask

kotlin {

// Set a name for your framework in a single place and reuse the variable

val libName = "my_library"

// Configure your Kotlin Multiplatform lib to generate iOS binaries

// NOTE: This will only work on Macs

ios {

binaries.framework(libName)

}

// You can choose your output directory

val frameworkDestinationDir = buildDir.resolve("cocoapods/framework")

tasks {

// Custom task to build the DEBUG framework

// ./gradlew universalFrameworkDebug

register("universalFrameworkDebug", FatFrameworkTask::class) {

baseName = libName

from(

iosArm64().binaries.getFramework(libName, "Debug"),

iosX64().binaries.getFramework(libName, "Debug")

)

destinationDir = frameworkDestinationDir

group = libName

description = "Create the debug framework for iOS"

dependsOn("linkDebugFrameworkIosArm64")

dependsOn("linkDebugFrameworkIosX64")

}

// Custom task to build the RELEASE framework

// ./gradlew universalFrameworkRelease

register("universalFrameworkRelease", FatFrameworkTask::class) {

baseName = libName

from(

iosArm64().binaries.getFramework(libName, "Release"),

iosX64().binaries.getFramework(libName, "Release")

)

destinationDir = frameworkDestinationDir

group = libName

description = "Create the release framework for iOS"

dependsOn("linkReleaseFrameworkIosArm64")

dependsOn("linkReleaseFrameworkIosX64")

}

}

}Here are two custom gradle tasks that build a “Fat” framework for debug or release. In this I have it outputting to the build/cocoapods/framework directory, but you can configure that as you like.

Gradle Task for “Fat” iOS framework

- Build a “Fat” debug version of the framework

./gradlew universalFrameworkDebug

- Build a “Fat” release version of the framework

./gradlew universalFrameworkRelease

Importing the iOS Framework into XCode

I previously wrote a blog post about how to do this which has a companion video along with it. 👇

Thanks and Related Resources

I didn’t figure this all out myself. I just got it to work for me and extracted out the bare minimum you need to make this work. Thanks to Swapnil Patil for letting me know that “Fat” frameworks are possible. Thanks so much to Marco Gomiero for his post Introducing Kotlin Multiplatform in an existing project.